Rolled Beef Sirloin Recipe with Porcini & Vermouth Sauce: Picture this: mushrooms sprouting wild across the moorland, cattle grazing peacefully among the junipers, their hooves tamping the earth. It’s a scene of rugged beauty that sets the stage for this dish. This rolled beef sirloin recipe with porcini sauce takes inspiration from that landscape, marrying the rich, earthy depth of porcini mushrooms with the robust flavour of grass-fed beef.

The sirloin, dry-aged and expertly rolled, is a thing of beauty. Coated in a fragrant juniper and thyme salt, seared to a golden crust, and roasted to tender perfection, it pairs effortlessly with the velvety porcini sauce – a symphony of wild mushrooms, vermouth, and cream. Serve it with a flourish and let the flavours of this heritage beef roast transport you straight to the moors.

Serves: 6

Prep time: 40 minutes

Cook time: 2 hours

Ingredients

Method

Roasting the Beef

- Preheat the Oven: Heat your oven to 170°C (fan).

- Prepare the Beef: Finely chop the juniper berries, thyme, and salt together until well blended, then mix in the black pepper. Generously season the entire sirloin joint with the herb salt mixture.

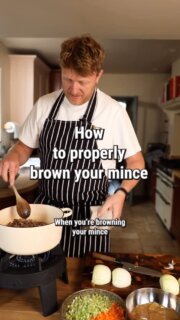

- Sear the Beef: Heat a little sunflower oil in a large saucepan over medium heat. Carefully and evenly brown the fat side of the beef joint. Remove and place the joint fat side up on a trivet in a roasting tray.

- Roast the Beef: Roast the beef in the oven until a meat thermometer inserted into the thickest part reads 49°C for rare.

- Rest the Beef: Remove the beef from the oven and allow it to rest for at least 20 minutes. Pour any resting juices into the mushroom sauce at the end.

Making the Porcini Sauce

- Rehydrate the Mushrooms: Place the dried porcini in a bowl and cover with boiled water. Allow them to soak for about 40 minutes. Once softened, remove the mushrooms from their soaking liquor, retaining the liquid for later.

- Cook the Mushrooms: Melt the butter in a frying pan over medium heat and sauté the mushrooms until tender and nicely coloured. Set aside a quarter of the mushrooms for garnish and keep the rest for the sauce.

- Cook the Aromatics: Add more butter to the frying pan and sauté the shallots and garlic until softened, about 12 minutes. Stir in the tomato purée and cook for an additional 3 minutes, stirring frequently.

- Build the Sauce: Pour in the vermouth and simmer until almost completely evaporated. Add the beef stock, reserved mushroom soaking liquid, and ¾ of the sautéed mushrooms. Simmer briskly until the sauce thickens to a gravy-like consistency.

- Blend the Sauce: Allow the sauce to cool slightly, then blend until velvety smooth. Return the sauce to the pan.

- Finish the Sauce: Stir in the cream and reserved mushrooms. Bring the sauce to a gentle simmer. If it appears too thick, add a little more beef stock. Taste and adjust the seasoning as needed.

Serving

- Warm the sauce and pour it over a warm platter.

- Slice the rested beef and arrange the slices in an overlapping line along the centre.

- Garnish with fresh parsley, tarragon, or both.